Top 100 Favorite Boxing Matches: #50-41

This is the sixth part of ten in my series of writeups on my favorite boxing matches. As we have officially reached the halfway point, I should preface exactly what I've said from the start. You are going to see many bouts that are genuinely incredible, will ask why it isn’t higher. I am not going to even bother justifying placements - from here, almost everything can conceivably be ranked as “one of the greatest fights of all time”. Hell, many of them are. It’s why I conceded I couldn’t craft an objective list, you simply can’t. But, make no mistake, these bouts are all must-watch - and even outside of the top forty, some of these are out of this world.

50 - Somsak Sitchatchawal vs Mayhar Monshipour (March 18, 2006)

An unfortunate commodity with combat sports history is that the international scene is underexposed. That is to say, a number of excellent pugilists and their history does not receive their due credit. The 2006 fight of the year between relative unknowns Somsak Sitchatchawal and Mayhar Monshipour was fortunate enough to receive one of those periodical spotlights. Monshipour, a man whose resolve was to press and throw, made it a firefight from the beginning and paid for it shortly thereafter by meeting the canvas. A regular person would have backed down, but this only seemed to drive Monshipour on. Sithchatchawal’s back was on the ropes for the majority of the contest from a seemingly unending barrage of punches, though surging uppercuts and consistent body work kept the fight an unbelievably chaotic brawl that escalated into a fifth that could only be described as stupid - and the ninth was frankly an entirely different level of bedlam as defense was completely foregone. As the Thai seemed to be breaking from the pressure in the tenth, his counter hook landed first and Monshipour was out on his feet.

49 - Earl Hargrove vs Donald King (May 22, 1983)

For whatever reason, Earl Hargrove and Don King - no, not that one - started their war before the bell. No effort to separate the two would expunge the tension whatsoever as the opening round ensued. A blistering amount of punches were exchanged without any restraint, King was dropped early, but he rallied in the final minute of an unforgettable first three minutes. From there, King took to smothering Hargrove, brandishing hooks to the ribs to slow down the more dynamic puncher, while Hargrove’s jab and straights snapped King’s head back time-and-time again. George Benton and Panama Lewis’ respective, chastising attempts to make both men fight a boxing match was inevitably given up by the midpoint as the two junior middleweights were only focused on who could inflict more damage. The eighth would exemplify this, but the dynamic power differences would be the decider, as Hargrove’s punches stopped King in the ninth in one of the more brutal bouts of the decade.

48 - Jung Koo Chang vs Hilario Zapata I (September 18, 1982)

Jung-Koo Chang was the kind of generational prodigy that stood out. Being called ‘The Korean Hawk’ was nomenclature for his swarming pressure comparable to contemporary to Aaron Pryor, yet he was stance-switching savant, excellent infighter, and dynamic genius. Chang was not even twenty years old and barely a professional of a few years before he challenged Panama’s defensive slickster Hilario Zapata for the WBC belt. Against Zapata, Chang engaged in one of the most aesthetic bouts on tape, as his natural abilities meshed with Zapata’s own for a sensational exhibition. Zapata proved he was not only an outside specialist, meeting Chang’s entries with counters all the way, but Chang’s speed commandeered the ring. His blitzes closed the distance too quickly, he bossed the inside despite the champion’s answers, and was competitive on the outside. The fight was close, but, in the view of this writer, the decision to the incumbent Zapata wasn’t the right one. Chang would rectify this is in a later bout - this was a rehearsal for what was to come for the greatest boxer Korea would see.

47 - Katsunari Takayama vs Francisco Rodriguez Jr. (August 9, 2014)

While boxing history tends to bring its largest competitors to the limelight, the same cannot be said about its smallest. Strawweight, the lowest male weight class, was primed by the fleet-footed WBC Champion Katsunari Takayama attempting to unify the division after a decade of being near its pinnacle. Known as ‘Lightning’ for a reason, Takayama moved as much as he threw - and he did both quite a bit. In his way stood a man younger by about ten years, one Francisco Rodriguez, but it was by no means an easy fight on paper. Rodriguez was known as a stepping stone for the impeccable for Roman ‘Chocolatito’ Gonzalez’s greatness; he wasn’t going to be that for another. No time was wasted, Takayama’s pace was set and Rodriguez was in pursuit - he had to keep up and step up to the task. In the second, Rodriguez made his read: that he could step in on Takayama’s combinations and counter on the separation. This earned him the fight’s lone knockdown in the third, but this only set Takayama off - by the end of the same round, his punches had Rodriguez’s nose bloody red. What followed is possibly the pinnacle of twelve-round endurance fights, as both competitors practically ran laps all over the ring, and the amount thrown increased exponentially. It seemed ludicrous on paper, but the final third would see them up the ante. Rodriguez decided that he wasn’t only going to outpunch his foe, he was going to outvolume him - in the ninth he would be coaxing Takayama back into the depths with him. Both obliged and equaled the other’s exertions, the only differences in a maelstrom of blows being that the person who kept moving forward was getting the better of it. There are really no words for it, it was a cartoonish series of exchanges - the final round being the most wild of the bunch. Maybe it was the bigger punches, but Rodriguez, despite Takayama’s sustained body attack, emerged with a decision whereupon he kept his own self-fulfilling promises.

46 - Edwin Rosario vs Jose Luis Ramirez II (November 3, 1984)

Edwin Rosario was a dynamo puncher for the lightweight division in the early 1980s with only one man surviving his onslaught, a Jose Luis Ramirez, whom had managed to fight him to a contentious decision loss. Ramirez, experienced as a boxer and tough enough to take shots from hard punchers, likely itched for a rematch. ‘El Chapo’ gave him one, this time with a title on the line, and then gave him a right cross at the start that set him down. Rosario wasn’t finished, he would press Ramirez relentlessly, bombing with the same power his challenger was intimately familiar with. Rosario sent him spiralling to the ground again in the second round brawl and it seemed inevitable that Ramirez was going to break from so many shots, but he just didn’t. Sooner or later, it was evident that the jab was saving Ramirez from more harm and that the puncher had expended too much energy. Ramirez dialed into punishing the champion’s ribs with a vengeance. A followup upstairs had Rosario reeling in the third as the tide completely shifted - it was a kill or be killed battle. Rosario had failed in his endeavor, but he lacked the same defenses to save himself the way his opponent had - Ramirez took over completely and the finish followed subsequently as the ref waved it standing.

45 - Matthew Saad Muhammad vs Marvin Johnson II (April 4, 1979)

The day Matthew Saad Muhammad, then Matthew Franklin, and Marvin Johnson met for a North American title is etched into the minds of any who witnessed as savage a fight boxing had ever seen. Nearly two years removed, Franklin and Johnson were set to collide for even higher stakes - a world title on Johnson’s belt in his hometown of Indianapolis. Anyone familiar with two of the most dogged to ever compete probably knew that the painful lessons of their first meeting would do little to dissuade them: another war was going to brew. Johnson, whom I’ve read was likened to a bull, knew only aggression from the moment the bell sounded. Johnson’s namesake, ‘Pops’, was no term of endearment - he had serious power in his hands. Even worse, he was a workhorse, never stopping his forward momentum until he was actually hurt. Against the talented Matthew Franklin, whose toughness was as psychotic as Johnson’s determination and had the physicality to contend, he had the perfect dance partner to produce another thriller. Johnson set the tone early and, by the end of the second, the two had picked up right where they left off. Franklin’s jab was essential as usual, but Johnson had refined his to be more effective than ever, spearing Franklin into covering up and then whipping his head around with hellacious hooks and uppercuts. A lesser man would back off, but Franklin’s legendary toughness held up - and he came back to test Johnson’s, bashing his rival with uppercuts and straights across the ring. There was no corner offered nor given on these punches - every one of them was thrown with murderous intent. Johnson seized the reins from the fourth onward, his patented uppercut-right hook combination hitting Franklin with blows that sounded like a cannonball had exploded in their vicinity. Johnson’s siege continued behind his lead hand, though the rib assaults kept him honest about overexerting too much in the firefight. The seventh seemed like everything was going as well as it could as Johnson managed Franklin at neutral range - and then a perfect cross had him staggered.

Johnson and Franklin sat in their corners for the eighth, evidently thinking the same - that this needed to end. Remembering the agony of the first encounter, both stood up, one with the desperation to not have the previous round’s ending repeat itself and the other seized by the scent of blood. One way or another, they were both right - this fight would end in the next three minutes. What followed can only be described as iconic, as they collided. Johnson’s punches richotched his challenger’s face around, but Franklin was firing back - and he wasn’t stopping, now forcing Johnson on the retreat.

The two most violent men in the world were unleashing and results were showing - Franklin’s visage was a claret-drenched portrait. And then Johnson fell. Franklin collapsed in the neutral corner, covered in wounds, staring only across to see if he needed to prove who he was. Johnson, too tough for his own good, did make it back to his feet, but it was over - it was waved as the name Matthew Saad Muhammad was finally christened in a throne forged from his own blood. It would remain there until his reign was over.

44 - Carlos Zarate vs Alfonso Zamora (April 23, 1977)

Imagine this: You have two bantamweight contemporaries from Mexico who were former teammates, now turned rival belt holders. They are both hellish punchers at best and, at worst, murderous finishers. They have been on a collision course for years, topped off by a singular statistic of 74-0 between them. And all but one of those wins were a finish. For national pride and spectacle, the clash between Carlos Zarate and Alfonso Zamora - “The Battle of the Z Boys” - was obviously not going to be your everyday anticipated matchup. The onlookers ringside were in a fever pitch, packing firecrackers and alcohol, police in riot gear watching closely in case someone chose to spoil the evening - and one particularly enigmatic person almost did. The Forum’s ring was no stranger to the tension, as the managers’ blood feud seemed almost as explosive as the fight itself was expected to be. But, one expectation was clear - even if not sanctioned as a title fight, this was going to be something.

A temporary interruption in concentration did nothing to throw off the laser focus of the Z Boys - the circling ended as a cross counter overhand and followup left hook kicked off the shootout. Zarate regained himself and charged back into the fire, his right straight forcing the same out of Zamora seconds later. They clawed at another like two wolverines over the last spoils of a hunt - it’s what everyone wanted and the only way it could end. There was only one key difference, even as Zamora’s swings rocked Zarate back a step - and it was experience. Zarate’s was showing in the form of a jab, a piston shotgun that caught the shorter Zamora out of range. In the surging waves of exchanges between two men whose red shorts obscured their similarities, this tool was changing the picture into one of clarity. Zamora was looking worn, Zarate pressed with rib-roasting murder in his expression. Zamora was soon on the pure retreat, now the hunted - he went down before the third round concluded. The fourth was a formality, as Carlos Zarate established the keystone victory of his career in one of boxing’s premier gunfights.

43 - Evander Holyfield vs Riddick Bowe I (November 13, 1992)

Previous amateurs-turned-professionals Evander Holyfield and Riddick Bowe entered their first meeting unbeaten, but there was plenty to prove for both. Holyfield, accomplished cruiserweight king, had doubters about the legitimacy of his throne even with his credentials. Bowe, the challenger, had even more scrutiny: a man who had talent for days could be hot or cold at random. Yet, on the biggest stage of all, Bowe came into the ring with a scorching presence and confidence - he was here to prove himself against a man who could do it all. Whatever shadow the two were covered in was lifted as a titanic battle was waged, one that Holyfield initiated. He jabbed aggressively, and threw his weight behind overhands and hooks as he closed the gap on Bowe. Soon enough, Bowe was meeting Holyfield’s advance with punches of his own, leading to some of the finest exchanges the division had ever seen in an all-terrain battle. That said, something was happening that perhaps no one expected - and it’s that Bowe was outhustling one of the hardest men of the generation. Bowe may have had a size advantage, yet he was more than able to match Holyfield with technique. His jab was landing with particular accuracy, he was fluidly outmanuevering a learned infighter up close, and he was landing noticeably more. Even if he had to take one to give his own, this did nothing to back Holyfield off - he had to bet Bowe would slow down in the war. Yet, the swelling on the champion’s face increasingly told another story; an overhand right in the seventh made him pause for the first time. Bowe was fighting the night of his life - leaving Holyfield resorting to brawling, where he had met his match. It seemed a matter of time before Holyfield fell. The uppercut to start the tenth round signaled the beginning of the end - except it wasn’t. One minute later, it was Holyfield pushing Bowe back for the first time since the beginning. His right was firing out with nothing but his pride on display - it was the manifestation of it.

Bowe was the better man that night, but the tenth was a reminder of who his opponent was in every way; it was Holyfield who won the final exchanges of the round. But, as said, the rest of the fight was Bowe’s though, as Holyfield went down in the eleventh. The challenger didn’t seem to lose a minute afterwards. If anything else, their meeting let both prove who they were and then some.

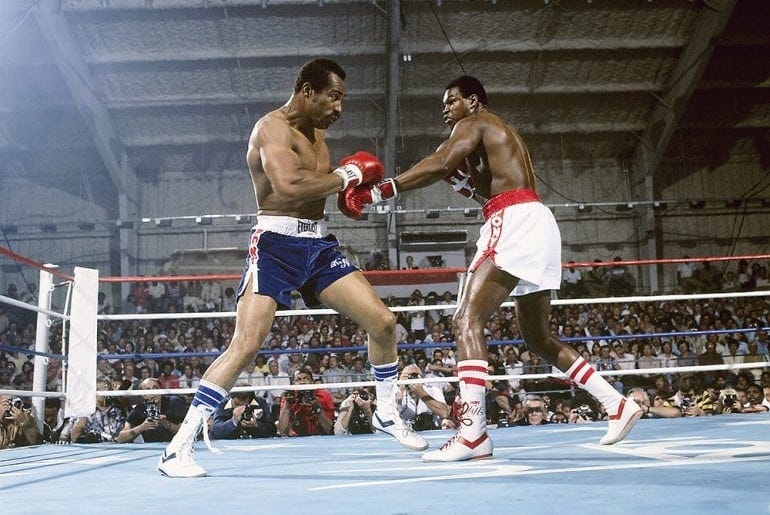

42 - Larry Holmes vs Ken Norton (June 9, 1978)

The clash between Ken Norton and Larry Holmes could well have been the passing point of the era - the end of the previous generation and signifying the start of the next. Ken Norton, trapped in a decade with Muhammad Ali and George Foreman, found himself as champion under bizarre circumstances, though that did nothing to dissuade him from his efforts to prove that he was one. Against Larry Holmes, a young Philadelphian with a stern resolve to prove himself as the new king, Norton took to being the aggressive vanguard of his pride and era. A flashing knife filled the space between them as Holmes’ jab made itself known - the Easton Assassin’s lead hand work was to be his career trademark - while Norton’s cross-armed guard caught blows in between attempts to pierce his armor. Holmes struggled to make his mark, but he was building points with his superior speed, his right cross flashing out almost as quickly as his left. Yet Norton was a spoiler, as he had proven by giving the great Ali all he could handle, and Holmes was in for a surprise as Norton did exactly what he had done to ‘The Greatest’ - outjabbing him. Norton’s looping hooks to the ribs and thunderous rights to the forehead followed and Holmes was on his bike as the chase ensued. Struggling to build momentum at distance, Holmes decided to try to take a risk as the fight entered its final third - stand in front of Norton. With the jab battle no longer going his way, Holmes banked on his power hand. Sure enough, blinding Norton with his lead hand to bomb him paid dividends for a devastating thirteenth, as over a dozen crosses, thrown with determined fury, had the champion looking for respite at the bell. Pressed to desperation himself, Norton resolved to come forward and win a volume battle - he took the fourteenth in the process. The fight was desperately close, had constant twists-and-turns - it was a showcase of brawn and brains, yet no one was ready for the final three minutes.

They saved their best for last - one of the greatest rounds ever. Norton simply doubled down on his already-Herculean surge, refusing to take a step backward. In response, Holmes punished Norton’s reliance on offense with counters. Gritting his teeth, Norton smashed Holmes with blistering hooks - the mouthpiece was out and blood replaced it. The challenger paused for a second, but then his own stubbornness reemerged, as he met Norton in the center and emptied his tank. The arms of the two were sagging, but it was the challenger who had enough left in the dwindling seconds. Norton was staggered - it may well have been the slightest difference on the scorecards to decide Holmes’ win - the start of the next generation - and to conclude one of the greatest of all heavyweight meetings.

41 - Naoto Takahashi vs Mark Horikoshi (January 22, 1989)

Korakuen Hall was a venue for warzones, whereupon Japanese boxers would test themselves in as ferocious national efforts that their competitive scene could find. Naoto Takahashi, whom we’ve already established as one of Japan’s greatest of action fighters, found his home here, even if it costed him insofar as longevity. His greatest of encounters then, was against one Mark Brooks, now Mark Horikoshi, in an absolute barnburner for the ages. With the national super bantamweight title on the line and both men, focused punchers with ridiculous fortitude, chaos seemed inevitable. The first was tame but the second was the opposite, as Takahashi hurt the champion. Pressing behind his jab, Horikoshi fought his way back into the now-emergent brawl with counters, managing to have Takahashi himself badly hurt at the end of the third.

The fourth round is simply carnage, as Takashi reverses the tide from being almost decked to sending his opponent down multiple times - both men are visibly wobbling the entire round in an astonishing three minutes. The fifth seems like a merciful breather, only to have Horikoshi hurt twice in the final minute. Takahashi’s pressure continued to win the battle in the sixth, his jab a constant factor. But the champion wasn’t done yet, he started to march forward himself, throwing heat when he could. His persistence seemed to pay off, as he began to outjab Takahashi in the seventh, and then downed him in a hellacious eighth - where he was taking tons of punishment himself. Something had to give for either - the ninth saw a series of knockdowns from Japan’s Comeback King allow for the advent of Takahashi’s reign as the super bantamweight crown. Unfortunately, it wouldn’t be easier to keep.

This concludes part six. Next time: Perhaps the most hipster-inclusive, contrarian segment of this entire project.